Keratoconus

What is keratoconus?

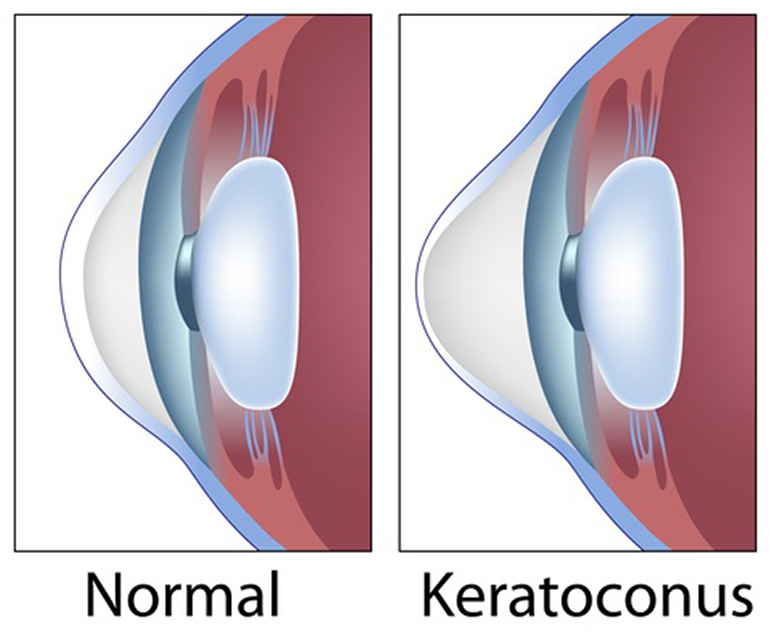

Keratoconus is a common corneal disease affecting up to one in 450 people. The cornea needs to be both transparent and appropriately curved to allow good vision. A normal cornea can be considered spherical (like a football) or ovoid (like a rugby ball). However in keratoconus, there is progressive thinning and steepening causing inferior sagging (ectasia) which compromises good vision.

What is the cause?

The cause of keratoconus is not fully understood, but there is likely a genetic component. It frequently occurs in isolation but can also be found in association with atopy (asthma, eczema and hayfever) as well as some other eye or whole body disease. The age of onset is rather variable depending on how it is looked for. Screening using corneal mapping scanners (topographers) picks up keratoconus in patients with no symptoms and at many ages. However, in terms of developing symptoms, it is a disease that typically starts in patients’ teens and twenties.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of keratoconus are essentially increased blurred vision and a changing spectacle prescription. An increasing myopia after the age of 23 or a large and increasing astigmatism at any age should alert an optician (optometrist) of the possible diagnosis.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is based on corneal mapping, although in the later stages there are characteristic physical changes evident on eye examination. An early diagnosis and treatment prevents these later signs.

What is the treatment?

In the early stages, optical management by stronger spectacles will improve vision, but as the disease progresses, "irregular astigmatism" results from the corneal distortion and this cannot be corrected with spectacles. At this stage, a contact lens will usually improve vision, but it will have to be a “rigid” or gas-permeable contact lens, which patient usually refer to as a "hard" lens. Although not particularly comfortable, the improved vision is very motivational!

However, neither spectacles nor a rigid contact lens will prevent keratoconus progressing. For progressive disease and provided that the disease is not too advanced (too thin), there is a new treatment called corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) to stiffen up the cornea and prevent further change. This treatment is typically carried out in an operating theatre and takes about 30 to 60 minutes depending on the protocol for one eye. CXL involves gently removing the superficial cells of the cornea which allows riboflavin (a B vitamin) to be applied and penetrate the deeper cornea. When the tissue is saturated, an ultraviolet light is used to induce a photochemical reaction (crosslinking). This makes the cornea structurally stronger and stops progression in the overwhelming majority of patients, thereby avoiding the need to do a corneal transplant with its associated risks. It is important to understand that the aim of CXL is not to make things better, but to stop them from getting worse. Nevertheless, in a small number of patients, some improvement is seen.

Once vision has been significantly compromised, a corneal transplant may be required to improve vision. Whilst deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) or penetrating keratoplasty (PK) are safe standard procedures, they are fairly major eye operations and the risks are much greater than for crosslinking. As a result, patients with documented progression are usually advised to have CXL before their disease gets too advanced for this treatment. This can occur because, as the disease progresses, the cornea becomes too thin for CXL treatment to be done safely.

If a corneal transplant is needed, the choice is between DALK and PK. Each has advantages and disadvantages. A DALK is a partial thickness procedure, and surgically more difficult to the extent that a number of patients have to be converted to a PK during the operation as a DALK has become impossible. Its disadvantage is that on average the best vision is not quite as good as after a PK. However it has the big advantage that rejection is extremely rare. In contrast, a PK is technically easier and is more likely to give good vision but with a greater risk of rejection. Most rejection can be treated successfully if the patient seeks medical care quickly, but each rejection episode prematurely ages the corneal graft. Both PK and DALK feel much the same to a patient and both need stitches which are usually taken out after 12-18 months once the cornea graft has healed. At this point, vision can be corrected further with spectacles or a contact lens.

A newer, less invasive partial thickness technique of Bowman’s Layer Transplantation (BLT) has been introduced to strengthen the cornea in advanced cases. This procedure remains an evolving field and may become a recognised technique for corneal surgeons.

In summary, the consensus amongst corneal specialists is that patients with keratoconus should have regular corneal mapping to look for progression, and if it occurs should be offered crosslinking (CXL). If you have or think you might have keratoconus, you should arrange for a corneal mapping scan.